The Path to Climate Leadership Starts in Low-Income Neighborhoods

Insights from Grid Forward 2020

GridFWD 2020, hosted by Grid Forward, convened energy service professionals from across the Pacific Northwest in an online forum to explore the many changes, perspectives, and solutions regional stakeholders are pursuing to support reliable, affordable electric service and the well-being of customers, co-workers, and communities. In this series of articles, Cadmus presents insights from experts at the conference and the solutions industry leaders are exploring to advance equity in resilience.

January 19, 2021

By Jeana Swedenburg

Competitive market drivers, state and local policy, and the increased availability of cost-effective energy supply alternatives are forcing utilities to consider opportunities for customer-centric renewable energy programs. Innovations in energy supply can drive solutions that not only advance the functionality of utility grid systems but also address systemic equity and access issues for all communities. Utilities must plan programs that address the needs of their most vulnerable populations in order to comprehensively address climate challenges. During a session at GridFWD 2020 entitled, “How Increased Grid Innovation Creates a More Equitable Future,” panelists discussed how they are engaging underrepresented communities in energy decision-making to pave a path forward.

Defining Equity

The Urban Sustainability Directors Network defined four types of equity for sustainability planning, decision-making, and program and policy design. These four aspects of equity are necessary considerations for utilities as they strive to make grid innovations that benefit all customers:

Transgenerational Equity: decisions consider generational impacts and do not result in unfair burdens on future generations.

Procedural Equity: inclusive, accessible, authentic engagement and representation used in the process to develop or implement programs or policies.

Structural Equity: decisions made with a recognition of the historical, cultural, and institutional dynamics and structures that have routinely given advantage to privileged groups in society and resulted in a chronic, cumulative disadvantage for subordinated groups.

Distributional Equity: programs and policies result in fair distributions of benefits and burdens across all segments of a community, prioritizing those with the highest need.

Transgenerational Equity: Future-Proofing Policy

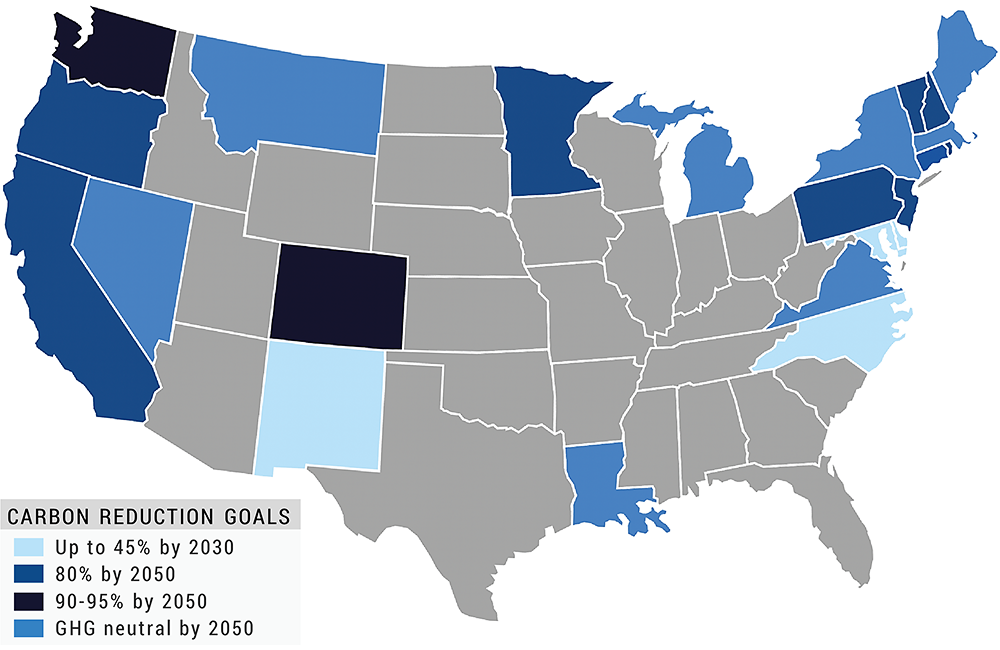

Across the United States, state legislators are pushing for a clean energy future for the generations to come. Currently, 23 states and the District of Columbia have established economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions targets that strive for significant carbon reductions (or, in many cases, carbon neutrality) by 2050 to reduce the consequences of climate change. Climate change poses significant economic, public health, and environmental risks to society and considerable evidence indicates that such challenges disproportionately threaten minority and low-income communities-communities that remain underrepresented in clean energy planning decisions. Because of this, many states are mandating that utilities consider these inequities when driving grid modernization and that they develop solutions to offer a clean energy future for all. Washington state’s 2019 Clean Energy Transformation Act outlines a plan for electric utilities to decarbonize energy production with provisions to ensure that clean energy benefits are equitably distributed. During GridFWD 2020, Debra Smith, CEO and general manager at Seattle City Light, said, “I love [the Clean Energy Transformation Act] because it’s a great example of how policy can be good and encourage growth and change. … [It] is designed as a policy to move [Washington] toward a clean energy future but to do so in a way that doesn’t leave anyone behind and allows all members of Washington state to reap the benefits of this clean energy transformation.”

This map includes economy-wide targets that were established either through statutory action or legally binding executive action (such as a governor’s executive order). Currently, 23 states and the District of Columbia have established economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions targets. Source: Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

Procedural Equity: Collaborating with All Customer Segments

Not only is offering equitable access to clean energy widely considered “the right thing” to do, it is also a practical necessity for achieving emissions reduction goals. According to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, almost half of the country’s rooftop solar potential is on low-income homes. As such, low-income voices must be part of the discussion to ensure the successful adoption of renewable energy technologies. As utilities set out to develop focused strategies for providing equitable access to clean energy, it is important for them to listen to members of frontline communities who experience the “first and worst” consequences of climate change.

During GridFWD 2020, Adjunct Professor of Practice at the University of British Columbia’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, Andrea Reimer, explained that utilities and governments can often present solutions to marginalized communities without first asking about the needs and values of those community members. Reimer specializes in community engagement and ensuring that residents have a voice in public policy. To actively engage marginalized communities, she says, “The first place to start is by showing up not because you want something, but just to show up.” Reimer said environmental advocates can push their way into low-income neighborhoods, stating, “You should take the [hydroelectric] dam, or you should take the solar, or you should take the wind because we know what’s best for you” without really listening first.

Reimer told a story about a group developing green building policy in Vancouver. These policy decision-makers were frustrated that builders from the affordable housing community were not engaging in scheduled meetings to discuss policy innovation. Upon hearing these frustrations, Reimer realized that the policy meetings were held at city hall, during the middle of the day, and were being hosted by English-speakers. All these factors made community engagement convenient for the decision-makers but challenging for local builders, who are predominantly first-generation Chinese and South Asian and whose jobs do not readily allow them to attend midday meetings. Reimer worked with these decision-makers to develop a plan so they could integrate into these builders’ communities to first hear how they feel about green building practices. She encouraged policymakers to meet with builders at their places of worship-a safe space where they feel culturally connected. After implementing this strategy, policy decision-makers realized that the builders were very interested in green building practices, and they are now an integral part of creating green building regulations. These builders are pushing for more stringent regulations and proposing ideas to accomplish greener buildings. Reimer emphasized, “Meet people where they are at-don’t draw people to your engagements. Go into their communities and listen to the engagements they are having and what issues they care about and listen, look, learn, and then figure out how to co-create some opportunities together.”

Structural Equity: Learning Lessons from the Past

Historical policy decisions, such as redlining, have created an undue climate burden for residents of low-income and minority neighborhoods. Across more than 100 cities, a recent study found that formerly redlined neighborhoods are 5 degrees hotter in the summer today, on average, than areas once favored for housing loans, with some cities seeing differences as large as 12 degrees. Redlined neighborhoods, which remain lower income and more likely to have Black or Latino residents, consistently have far fewer trees and parks that help cool the air. They also have more paved surfaces, such as asphalt lots or nearby highways, that absorb and radiate heat.

These policy implications make climate a gentrifying concept that further drives neighborhood-based inequity. Some properties become more valuable than others due to their ability to better accommodate settlement and infrastructure in the face of climate change. For example, residents with financial means may move away from the aforementioned inner-city communities that experience extreme heat and seek refuge in suburbs with cooler temperatures. This causes an undue burden on lower-income households as suburban property values increase and inner-city housing prices become devalued. Conversely, rising sea levels and flood risks may push residents from previously desirable coastal communities inland. A 2018 study found that the value of higher elevation property in Miami-Dade County rose from 1971 to 2017 while that of lower elevation property declined. Utility grid resilience efforts and system innovations to prepare for a changing climate should consider more than just infrastructure updates, because adding resilient infrastructure may also cause additional gentrification as the more advantaged move into less risky areas and force underprivileged residents out.

During GridFWD 2020, Smith discussed how Seattle is evolving in this area: “We do see the opportunity to rebuild our city in a way that is… more racially just, more environmentally equitable. We are doing a lot of work right now across the city… [to] reimagine the space in ways that honor all the people that live here.” The Urban Sustainability Directors Network published an example of how Seattle took action to address inequity that improves services for everyone: a story of streetlight repairs. Like many cities, Seattle’s public works department historically repaired streetlights upon request. Residents would phone in complaints and city workers would show up and replace light bulbs. This process left poor neighborhoods in the dark: more streetlights in low-income neighborhoods were in disrepair than streetlights in other areas of the city. Because the life span of a streetlight bulb is predictable, the city changed its process and is now fixing streetlights on a regular schedule. This addresses the inequity across neighborhoods and benefits everyone, including wealthier residents who no longer have to call the city to make a complaint. By addressing the needs of the least well-served neighborhoods, everyone benefited.

Distributional Equity: Understanding Determinants of Disparity

Reimer encouraged attendees of GridFWD 2020 to remove the obstacles that keep marginalized communities from enjoying the benefits of clean energy rather than creating short-term solutions for access. In 2019, Tony Reames, director of the Urban Energy Justice Lab at the University of Michigan, defined energy justice as “fair and equitable access to energy technology [and] fair and equitable participation in energy decision-making.” Reames indicated that energy is a basic right because it is so important to everything we do in life, which means energy needs to be affordable, clean, and efficient. Low-income households struggle with rising energy costs, yet, as Reames’ research shows, they often have the least access to energy-efficient or clean energy technologies.

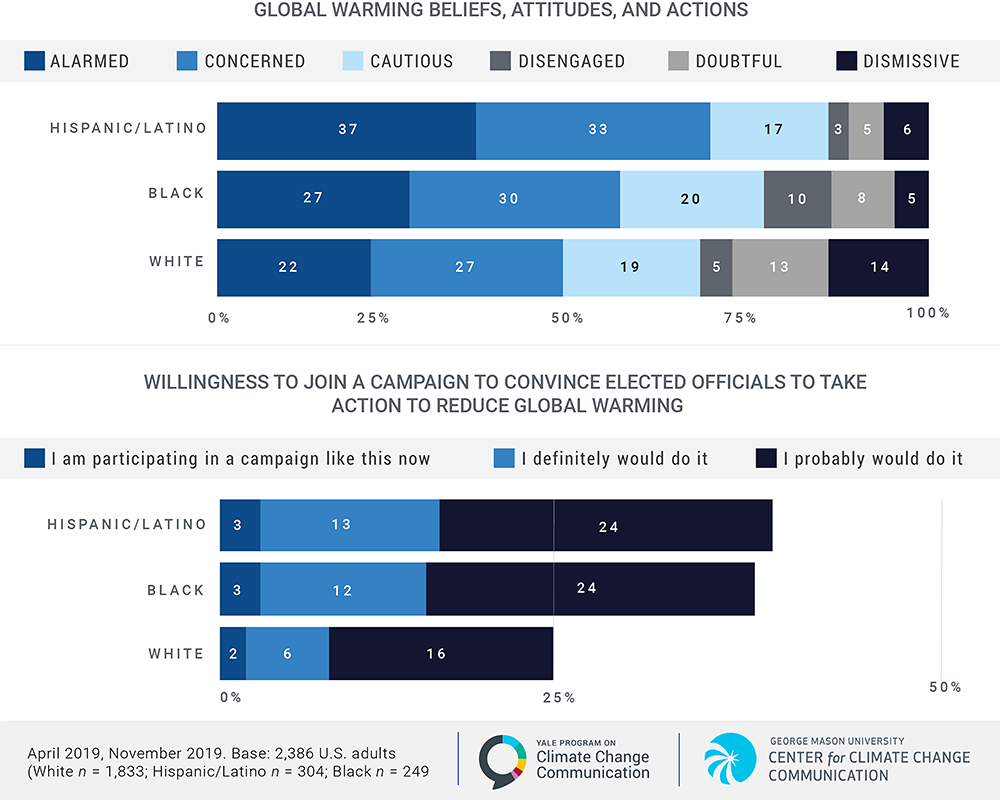

For equity to have meaning, it must be connected to an understanding of how group identity shapes people’s lives. To achieve energy justice, utilities must not only consider customer segment economics but must also identify the specific demographics of those within a community who need to be fully engaged and whose opportunities and access need to be improved. Several customer groups are most impacted by policy decision-making and have life outcomes that are disproportionately affected by the existing structures in society: people of color, individuals with limited English proficiency, and age outliers (the young and the elderly). According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, of those who are struggling to afford their energy bills in the United States, about half are Black and 40% are Latino. This is true despite the fact that ethnic minorities are engaged clean energy advocates. Prior research shows that people of color in the United States are more concerned than white Americans about climate change. Latinos, in particular, are much more engaged with the issue of global warming than non-Latinos. Latino Americans are more convinced that global warming is happening and is human-caused, are more worried about the situation, perceive greater risks, are more supportive of climate change policies, and are more willing to get involved politically than Americans of other ethnicities.

Listening to members of disenfranchised communities and designing clean energy programs and policy that are accessible to all is the clear path to energy justice and climate leadership. To improve climate change action across diverse audiences and more effectively support public engagement and adoption, it is imperative to conduct customer research that goes beyond understanding whether customers participate, but that also explores what renewable energy options customers want and how and why they take certain actions within the context of a renewable energy program. As Reimer said, “If we are [designing solutions] exactly the same way in a clean energy world as we were in a dirty energy world, we’re probably not moving that far ahead.” It’s time to listen up.

More GridFWD Insights

Utility Resource PlanningEquitable Resilience in the GridA look into the state of power outage resilience for disadvantaged communities across three at-risk regions in the United StatesUtility Resource PlanningThe Role of Wholesale Markets in Grid DecarbonizationLessons from the Western Energy Imbalance Market